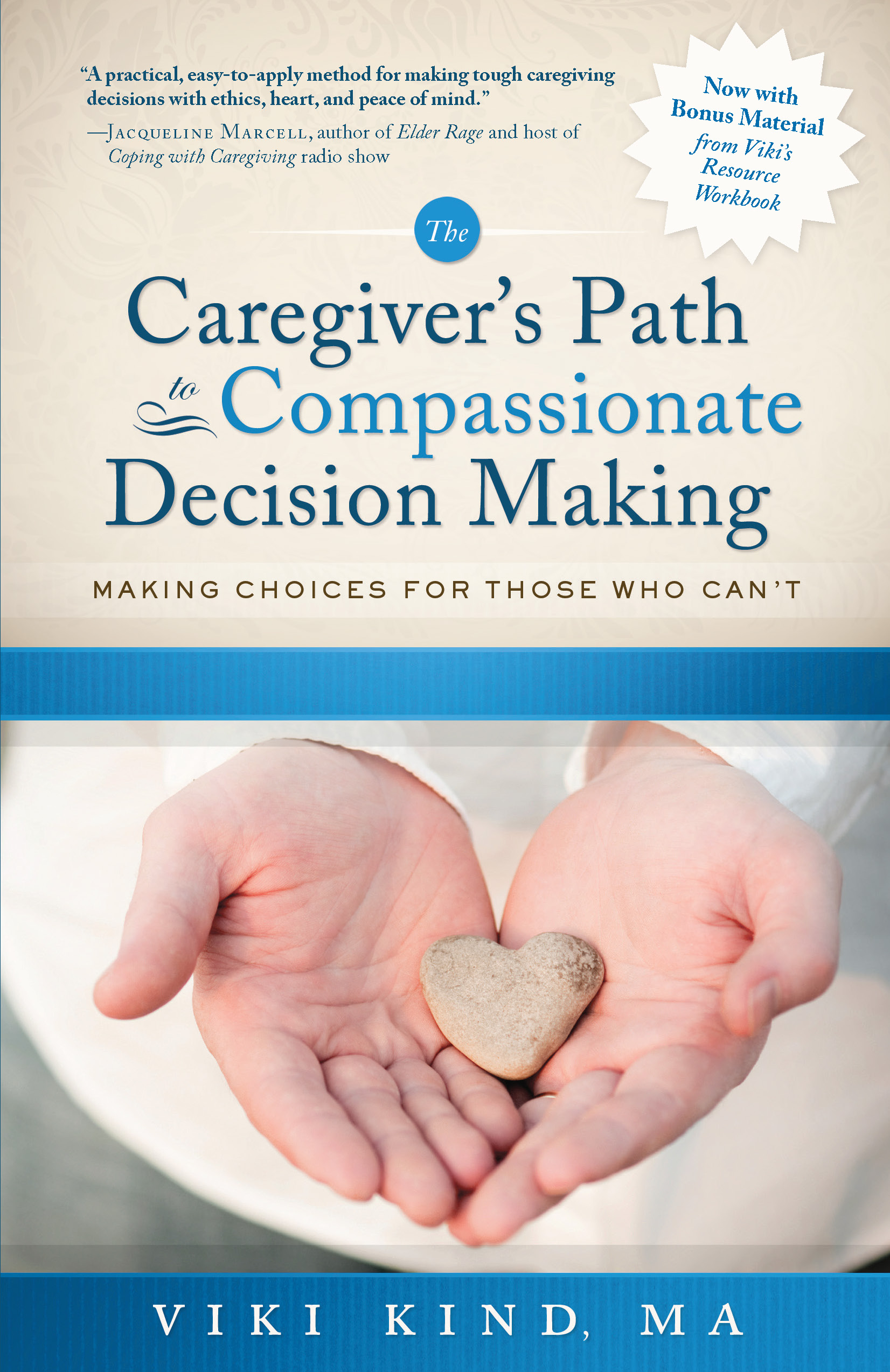

New Edition – Award Winning Caregiver’s Path to Compassionate Decision Making – only at Barnes and Noble

October 18, 2018 by Viki Kind

Filed under Ethics In Action, Featured

AVAILABLE ONLY at Barnes and Noble Caregiver’s Path ebook and print book

Recommended by:

- Journal of Gerontological Social Work

- Pain Management Nursing Journal

- Journal of the Catholic Health Association of the United States

- Alzheimer’s Association

- Stanford University School of Medicine Chair – Moira Fordyce MD, MB ChB, FRCPE, AGSF, Geriatrician – Adjunct Clinical Professor

- NAMI Advocate – National Alliance on Mental Illness

- Harry R. Moody, Ph.D., Director of Academic Affairs, AARP

- Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation Paralysis Resource Center

- Muscular Dystrophy Association

- Journal of Hospital Librarianship

(Second edition says “Bonus Material” on the cover.)

You know how difficult—even heartbreaking—it can be to make decisions for someone with dementia, stroke, Parkinson’s, developmental disability, mental illness, or other brain injury. Feeling confident that you’ve made the right decision would be a welcome relief from the worry and guilt you may be feeling.

The Caregiver’s Path is an invaluable resource for caregivers struggling to make the right decisions, whether it’s taking away the car keys, moving to a long-term care facility or making the difficult medical and end-of-life choices.

A simple, step-by-step process which adjusts as your loved one’s mental capacity changes:

- Guidelines to help you determine if your loved one or patient can make decisions, who should make the decisions, and how to make better decisions

- Questions to use in almost any medical or quality-of-life situation that will help you gather all of the information you need

- Techniques for improving communication between patients, families and caregivers

The Caregiver’s Path provides tools and strategies to help answer the question, “Am I doing the right thing?”

“An excellent guide for families left struggling and feeling overwhelmed when making decisions for those who are incapacitated. The tone is conversational, examples familiar and explanations simple and clear. With comfort and assurance, decisions are made systematically, while respecting the wishes of the individual. Every caregiver should read this guide before there is a crisis.” Edna Ballard, MSW, ACSW, Duke Family Support Program; senior fellow, Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development; Bryan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center

“It is a valuable resource that covers information needed to make all levels of decisions. I have never found this information discussed in such a clear, compassionate manner. GET THE BOOK.” Carol E. Pollard, RN, LMT

4th Edition Available – Resource Workbook, Visual Tools and Conversation Guide

November 22, 2014 by Viki Kind

Filed under Featured, For Healthcare Professionals, For Patients & Families

WORKBOOK AVAILABLE ONLY BY CONTACTING VIKI DIRECTLY

I am excited to let you know the 4th edition which has 12 new pages of uniquely designed visual conversation tools is now available. It includes articles, worksheets and templates you can copy and share to help with issues such as evaluating danger, making challenging medical decisions, managing caregiver burnout, and communicating your end-of-life wishes. – Order here or email Viki directly. Resource Workbook, Conversation Guide and Visual Toolkit 135 pages (8½ x 11)

Usually $40 – SPECIAL: $34.95 plus sales tax and shipping

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- Section 1: Medical Decision Making Tools

- Crisis Planning Worksheet for Urgent Decision Making

- Quick Tips for Crisis Decision Making

- Drawing an Outcome Roadmap Article and Diagram

- Recovery is Not a Straight Line – Managing Expectations

- Weighing the Options – Risks, Benefits and Burdens

- Weighing the Options Exercise

- Is the Patient Willing to Endure the Burdens to Get the Benefits?

- Double Weighing the Options Exercise

- Combining an Option Roadmap with the Risks, Benefits and Burdens When Discussing the Alternatives Article and Diagram

- Two-Hand Test for Medical Decision Making

- Two-Hand Test for Medical Decisions Making Diagram

- Evaluating Medical Options Through Three Lenses

- Evaluating Medical Options Through Three Lenses Diagram

- Sliding Scale for Acceptability: Where are the Patient’s Boundaries?

- Sliding Scale for Acceptability Exercise

- Evaluating Treatment Options When You Know the Patient’s Long Term Goals Article

- Evaluating Treatment Options When You Know the Patient’s Long Term Goals Algorithm

- Four Boxes Motivation Article and Exercise – Exploring Why thePa tient Isn’t Following Your Treatment Plan

- 5-Step Process to Help the Person Get Out of Denial

- Questions to Ask When Making Medical Decisions

- 6 Tips to Improve Communication with Your Doctor

- Getting Ready for Your Doctor’s Appointment

- Section 2: Evaluating Danger and Risk Tools

- Can the Person Connect the Dots?

- Evaluating Danger and Risk When Making Decisions

- Evaluating Risk for Those Without Capacity Diagram

- Evaluating the Dangers Worksheet

- Solutions to Creating a Restraint-Free Life

- Section 3: Caregiver Conversation and Support Tools

- Are You Care-grieving?

- The Ladder Diagram – The Caregivers Needs Count Too!

- Using the Ladder Diagram

- How is Your Relationship Now That Illness is a Part of Your Lives?

- Viki Kind’s 4-Step Process for Asking For and Accepting Help

- 4-Step Process for Asking For and Accepting Help Worksheet

- Caregivers and Guilt

- How to Say “No” Handout

- Section 4: End-of-Life Conversation Tools

- Insider’s Guide to Filling Out Your Advance Healthcare Directive

- Quick Tips for Filling Out Your Advance Directive

- Quality of Life Statement Template

- Viki’s Quality of Life Statement

- Guidance for My Decision(s) Maker

- What I Want My Doctor to Know About My Faith and/or Culture

- Having My Doctor Review My Advance Directive

- 5 Quick Tips for Making the CPR vs. DNR Decision

- Avoiding the Pitfalls in CPR vs. DNR Decision Making

- Recommended Books and Additional Resources

- Acknowledgements

Getting Caregivers to Ask for Help – Viki’s Four-Step Process

January 20, 2012 by Viki Kind

Filed under Featured, For Healthcare Professionals, For Patients & Families, Newsletter

Too often we underestimate the power of a touch, a smile, a kind word, a listening ear, an honest compliment, or the smallest act of caring, all of which have the potential to turn a life around. Leo Buscaglia

I have never been very good at asking for help and like many family caregivers, I didn’t think that my own needs mattered. Thinking I had to do everything all the time caused me to have two breakdowns; once during my early years of caregiving and again the last year of my caregiving journey. (I was a caregiver for over 17 years.)

I wish I had known about the following statistics from the MetLife Study:

Family caregivers experiencing extreme stress have been shown to age prematurely and this level of stress can take as much as 10 years off a family caregiver’s life.

40% to 70% of family caregivers have clinically significant symptoms of depression with approximately 25%-50% of these caregivers meeting the diagnostic criteria for major depression.

Stress of family caregiving for persons with dementia has been shown to impact a person’s immune system for up to three years after their caregiving ends thus increasing their chances of developing a chronic illness themselves.

I don’t know which statistic frightens me the most. But I do know that I have paid an emotional, physical and financial cost for being a caregiver. (I also loved taking care of my family.)

But it didn’t have to be that way. I could have and should have asked for help. But I am a caregiver and when people told me, “Just make time for yourself,” it wasn’t that easy.

If you think about who in a family becomes the caregiver, it will usually be the person who is more nurturing and generous with their time. So by nature, the caregiver is the type of person who already gives more than others. And this becomes a vicious cycle of give – give – give instead of give – receive – give – receive.

I recently said to my friend who is an overwhelmed caregiver, “Maybe now is a good time for the rest of your family to learn what they need to do to help their grandfather.” What I heard back from her were lots of excuses:

They don’t want to help

They don’t know what to do

They don’t know him like I do

They will just make it worse

I don’t have time to teach them

It is just easier if I do it

I get tired of asking

I don’t think they would help, even if I asked

Why should I have to ask, they should just know what to do

I don’t want to be a bother

It is too much effort to ask

Sound familiar? I realized in that moment that it isn’t always that the family won’t help; it is the caregiver who is resisting asking for help. So let me ask you. If you had a broken shoulder, would it be okay to ask someone to carry your groceries to the car? If your car broke down, could you call for a tow truck? When your loved one needs help, don’t you get them the help you need? Then why don’t you deserve the same attention? Your needs matter and you deserve to have someone help you.

Viki’s Four-Step Process

Step 1:

I encourage you to explore what is keeping you from asking. Write down what goes through your head when someone says, “You should just ask for help.” What are your resistance statements?

Step 2:

Take your list of resistance statements and put a statement beside it to help you get past what has been preventing you from asking for help. Here are a few examples caregivers have come up with:

They don’t want to help – Well I don’t know this because I haven’t given them a chance

They don’t know what to do – I could teach them

I don’t have time to teach them – You don’t have time because nobody is helping you. If you teach them now, then they can help at other times in the future.

It is just easier if I do it– Only the first time.

Why should I have to ask, they should just know what to do – Would I have known what to do before I became a caregiver? Then how would they know?

I am not saying you will be able to get past your barriers right away, but you need to begin so you won’t break down like I did. One thing that helped me was to realize that the other person won’t do what needs to be done as well as I would. They may do things slower, awkwardly at first, and in their own way. But that is okay because you are going to get free time and your loved one will be okay.

Step 3:

Make a list of all the things that would help you such as practical, emotional, financial and information support. Write a really long list and carry it with you so when people say, “What can I do to help?” you can pull out the list, hand it to them, and ask them what they would like to do.

Ask for specific things:

Can you call mom each week and ask her about her favorite memories or talk to her about what is worrying her?

Can you call me every day to check on me? (This can be very helpful to keep your depression under control.)

I don’t have time to read this book about Maria’s disease. Can you read it and then send me the main points?

Can you research what is the best wheelchair to buy?

People can help from a distance:

Can your brother listen to Dad’s doctor’s appointment by speaker phone?

Can they do the shopping for groceries online and have the food delivered?

Could they pay for someone to come to the house to give you a massage?

Can they take over paying the bills or set up automatic bill pay for you?

Can they send $51 a month so you can pay for three hours of respite care?

Ask someone to create a phone tree to disseminate information. This way you don’t need to make all the calls. Have others spread the news.

Local help:

Mom needs a ride on Thursday for her haircut.

Could you pick up some milk and eggs when you go to the store today?

I need someone to come and clean my kitchen.

Can you sit with Bob on Thursday night so I can go to a class about coping with dementia?

These are just a few ideas. I am sure you can come up with lots of ideas, big and small. (Don’t hesitate to put everything on the list. You will be surprised by what people are willing to do.)

Step 4:

Ask a lot of people. You may need to ask 5 people to find one that will help you but that is okay because now you have one person who will help you. Ask people for things they can actually do. Different people have different abilities. Show them the list and let them choose what they would be comfortable doing. Tell them the deadline for when the task needs to get done.

Oh no, I hear your resistance statement coming through. “There is nobody I can ask.” Here is my response to break through your resistance. There are more people in your circle of friends, family and community than you think. Call a local faith community and ask for help. (You don’t even need to belong to that church or synagogue.) Call the Area Agency on Aging in your town and tell them what you need. They can help connect you to resources. Tell the people in the hair salon about the struggles you are facing and maybe they know someone who can help. Many high schools are requiring kids to do community service hours. Call the school and ask to have someone assigned to help you.

It may feel like a lot of work to begin to ask, but don’t let this stop you. This is another of those resistance issues. Remember that you are not just asking for this one time, you are training this person for the future. If you can get them to trained and used to helping, they might be able to help you every week or two.

Lastly, give gratitude even when you think your family should feel obligated to help. Of course they should but let’s be realistic. Our practical goal is to get them to help more than they have been. Saying thank you and giving words of appreciation go a long way to reinforce good behavior. And if that doesn’t work, you can always say, “If you don’t have time to help, then you are going to have to pay to hire someone to help me.” That will get their attention.

Have a kind and respectful day.

My New Quality-of-Life Statement to Attach to My Advance Directive

January 3, 2012 by Viki Kind

Filed under Featured, For Healthcare Professionals, For Patients & Families

The goal of writing a quality-of-life statement is to have it express your personal preferences and to have it sound like you. One of the problems with many of the legal/medical forms is that they all sound alike and they don’t allow your voice to be heard. I encourage you to use the categories I have listed below to express what you would want people to know about you if you were too sick to speak for yourself. You can use some of my language from my document below if you would like but my goal is for you to make it personal and meaningful to you. You will know you have gotten it right if people say to you, “Yes, this is sounds like what he/she would say.” By making it feel personal, you will help your family/friends feel more confident that they are truly honoring your wishes.

Sections of QOL Statement to Consider Including in Your Directive:

? Types of illnesses where this advance directive would apply.

? What is important to me?

? What conditions would I find reprehensible to live with long term?

? CPR, ventilator and feeding tube preferences.

? Reassurances for the decision maker.

? What is a good death in my opinion?

? What I want the doctors know about honoring my religious/cultural beliefs both while I am sick and/or dying?

Here is my new quality-of-life or meaningful recovery statement. My wishes haven’t changed but how I am saying it is much more complete. Feel free to take any part of it you would like. Use the basic headings and then make it personal and meaningful for you. I would recommend attaching it as an addendum to a basic advance directive form that works in your state.

Advance Healthcare Directive for Viki Kind – dated 11/1/2012

Types of illnesses where this advance directive would apply whether I am terminal or not terminal.

I can never list every type of disease that might make me begin to lose my mental capacity but the list might include, but not be limited to: all types of dementias, stroke, brain injury, mental illness, anoxic event, etc. I don’t have to be completely out of it like being in a coma, persistent vegetative state, or minimally conscious state for this document to go into affect. And I don’t have to be terminal. The point is that I don’t want to have my life prolonged/sustained if my brain no longer works well enough to enjoy what is important to me.

What is important to me? (The loss of any of these might be enough for my decision maker to implement my wishes documented in this advance directive.)

To make a difference in the world.

To be able to communicate with those I love.

To receive the joy that comes from personal relationships.

To have some independence.

To be able to give love, not just receive people’s kindness.

To not be a burden on my family/friends – financially, emotionally or physically.

To have a good death as defined by me (see below).

What conditions would I find reprehensible to live with long term? (Please give me the chance to recover if recovery is possible, but if I am not recovering to a level of functioning that I would think is worthwhile, whether terminal or not, then choose comfort care and hospice which I understand will lead to my death.)

All of the following conditions do not have to be present at the same time for the decision to be made to allow me to die from my illness/injury. Any one of these conditions may be sufficient enough to change my course of treatment from prolonging my life to comfort care and allowing a natural death.

This list of “Conditions I would not want to live with” includes but is not limited to:

Not recognizing my loved ones.

Not being able to communicate by voice, computer or sign language.

Wandering around aimlessly.

Suffering that isn’t necessarily pain related.

Significant pain that can not be controlled.

Significant pain that requires so much medicine that I am sleeping all the time.

Having to live in a skilled nursing facility or sub-acute facility permanently with my cognitive impairment. Nursing homes create such sadness in me every time have I visited or have stayed overnight with a loved one. I am too empathetic and take in people’s suffering too easily to be in that environment. It would destroy me long term. A short-term stay in a SNF/rehab/sub-acute is okay if I can recover to a life that I would consider worth living. (I understand that with certain types of traumatic brain injuries, they take a longer period of time to evaluate whether or not recovery is possible.) But if it looks like I am not recovering, then no thank you.

Okay, now the CPR, ventilator and feeding tube conversation.

My overall guideline is that if CPR, ventilator support or a feeding tube/TPN can return me to what I would consider to be a meaningful existence, (what is important to me), then please give me CPR, ventilator support and/or a feeding tube/TPN. But there has to be value in these medical options and any other medical treatment choices that are being considered. Don’t do things, including but not limited to, antibiotics, etc., that are just to sustain my poor condition.

I am not opposed to living with a feeding tube/TPN if it gives me many years of being able to enjoy what is important to me. But if the feeding tube/TPN is just to sustain my miserable condition, (what I would consider reprehensible) then don’t put it in or give me feedings through it; and please take the feeding tube out if it is already in. (Okay, if I am on hospice and the feeding tube gives you access for administering the pain and suffering meds I need, then you can leave it in. But don’t put food or additional liquids in it.) The feeding tube, like all medical decisions, needs to create value in my life, not just sustain my life.

If I am still healthy and can still experience lots of the things that are important to me, then give me CPR. But as my health declines and CPR becomes less statistically successful, then make me a DNR. Just like many doctors, I don’t want to die by CPR. I want to die peacefully without life-prolonging medical interventions. (Doctor, please ask yourself the surprise question: Would I be surprised if Viki died during this hospitalization or died in the next 6 months? If the answer is “No, I wouldn’t be surprised,” then talk to my decision maker about end-of-life choices, including putting me on hospice.)

Reassurances for the decision maker

You are allowed to make the best decisions you can based on the circumstances and what you know at the time. You do not need to know for certain or absolutely that you have all the answers. The decision doesn’t have to be perfect. Use your heart and your head. I trust you to do the best you can. (Ed, you don’t have to go into super-perfectionist mode.)

I believe love does not obligate a person to sacrifice themselves to be the caregiver for another. The damage done to the caregiver, emotionally, physically and mentally is too costly. I do not expect someone to give up their mental, emotional and physical health for me. Look at the MetLife studies. Caregiving sucks. And I love my decision maker and alternates too much to impose such a burden on them.

(Ed, if you need some time to make peace with what has happened, then you can take the time you need. I don’t want the decision to feel rushed or uninformed, which would cause you a lifetime of regret.)

For you doctor, your role is to give my decision maker as much information as you can so he/she can make an informed decision. I encourage you to share your wisdom, guidance and experience but ultimately, it is my decision as expressed through my decision maker and this document. Remember, this document is an act of autonomy and should not be ignored by my decision maker/s, other family members, doctors or worst case, the courts. (I will definitely come back and haunt a judge who isn’t respecting my wishes.)

What is a good death in my opinion?

I would prefer to die at home but I realize that sometimes, a person needs to die somewhere else so I accept that. I would like to have my family/friends with me which includes and is limited to those I interact with on a regular basis. Those family/friends who have chosen to not be in my life while I was living should certainly not be there as I am dying. Because I like control over my life, I would like to be able to clean up my desk and to get my financial information updated. I would like to be able to write love letters, record messages and to say my goodbyes. (I will do my Go Wish Cards and leave a copy for my family.)

I would like to die with reasonable pain control. For the days leading up to the death, I would be willing to tolerate a certain amount of pain if that allowed me to have meaningful time with family/friends. But at the end, there had better be no pain and definitely, no air hunger. (That doesn’t mean ventilator support; it means manage my air hunger with medications.)

And you better not be force feeding me by mouth, by IV or by tube as that would increase my suffering. (And that includes you at the skilled nursing facility, sub-acute facility or other care community if I happen to be dying there. I know you have your regulations but I also know you can’t assault someone with food if they have said no when they had capacity.)

That’s it for now.

Viki Kind ________________________________

Date: 11/1/12

GO WISH Cards – A wonderful tool to explain what you want if you were seriously ill

Coda Alliance presents the ‘Go Wish Game’. It gives you an easy, entertaining way to think and talk about what’s important to you if you become seriously ill. The starter game comes with two packs of cards in contrasting colors and instructions for using the cards individually or in pairs.

For more information about the game, and to play on-line, visit www.gowish.org.

Reach And Teach Says:

“A woman at church came up to us and thanked us for having introduced her to Go Wish. She had given her mother a deck of Go Wish cards and had gone through the deck once with her mom. A month later, her mom had fallen into a coma, and her children were facing very difficult decisions about her care. They disagreed with each other and there was a lot of tension. One of the children had to go to the mother’s home to get something and found the sorted Go Wish card deck and detailed notes the mother had written about her top ten wishes. It was clear what their mother wanted, and the children were relieved to be able to follow her wishes, clearly documented, rather than having to argue with each other about what they each thought their mother might want.”

We feel very lucky that our paths crossed with the amazing people at the Coda Alliance. Having seen what we had done with Teaching Economics As If People Mattered, CIVIO, MicahsCall.org, Tikkun/NSP, and other online projects, the Coda Alliiance asked us if we could help create an online version of Go Wish. We feel that having your desires known and followed, especially when you can not speak for yourself, is a key social justice issue.

Go Wish helps you figure out what’s most important to you and allows you to have discussions about your wishes with people who may someday have to speak for you. If you are a caregiver, or may find yourself in that position, Go Wish is also a very good way for you to learn, ahead of time, what the person you may be caring for wishes. We’ve found the cards incredibly helpful in our own lives as we work with our own aging parents, and when we have shared them with others they have had significant impact.

We’re grateful to have the Coda Alliance as one of our 10/10 partners, helping to make the Go Wish card decks more easily available across the country.

Your Order Includes: You get 2 decks (two different colors) for $22.00 (which includes shipping within the United States – for international orders, please select “International Shipping” from the pull-down menu and we will add $10 to cover the additional postage).

Bulk Orders: Card packs may also be purchased in bulk in quantities up to 64 packs total. Use the pull-down menu to select bulk order quantities. Prices include shipping and handling.

If you’d like to order larger quantities, please call us at 1-888-PEACE-40.

Order Directly from the Coda Alliance:

You can also order decks directly from the Coda Alliance. They have special pricing for very large bulk orders.

https://www.reachandteach.com/store/index.php?l=product_detail&p=557

Have a kind and respectful day.

Drowning but can’t reach for a life vest: families, caregivers, doctors, nurses and many others helping professionals

January 4, 2011 by Viki Kind

Filed under Featured, For Healthcare Professionals

I had such a sad experience recently. I was speaking to a group of doctors and presenting them some techniques to make their lives easier. (This was at a county hospital which deals with the most underprivileged of our community.) I was surprised by how many of the doctors in the room were so resistant to accepting help. I sensed from their comments how burnt out they were and how hopeless they had become. The system they are working under is so broken that they couldn’t imagine that anything could change or be made better. It was painful to witness their suffering.

I realized that what I was seeing was classic caregiver burnout aka compassion fatigue. Caregivers, both family and professional, get so overwhelmed, they can’t ask for help. Lifeguards see this all the time when the person becomes so fatigued that the person can’t grab hold of the life vest right in front of them. The lifeguard has to swim out to the person and literally carry them to shore.

It is so easy for those of those of those who help caregivers to just say, “Grab on and I will help you,” but it may be too late. Ideally, we should reach the person before they are that far gone, but often times, the burnout doesn’t reveal itself until it has become extreme.

I understand this. When I was caregiving for my fourth and final relative, I became so overwhelmed that I laid down on the sidewalk in front of my house, and couldn’t get up. The only reason I finally did get up was because I didn’t want someone driving by to panic and call an ambulance. (Typical caregiver behavior, I was more worried about everyone else, before myself.) I went in the house and cried for days. I was lucky because my husband was my life saver and helped me reach out for support. For so many caregivers, they are drowning and don’t know help is available or where to turn.

For healthcare professionals, there is pride in being strong and capable, and to be weak is professionally unacceptable. And because their colleagues rarely express their own suffering, these professional caregivers think they are all alone. This leads to even more isolation and inability to ask for help.

I would encourage those of you who work as a professional healer to make sure your organization develops programs and support groups for you. You deserve the same care that family caregivers are receiving in the community. I need all of you to be okay because a lot of people are depending on you. But I don’t expect you to be super-human, I understand you are very human and have the same needs as all the rest of us. Please realize you are not alone and there are people ready to help. A great organization that can help is http://www.compassionfatigue.org/.

Have a kind and respectful day.

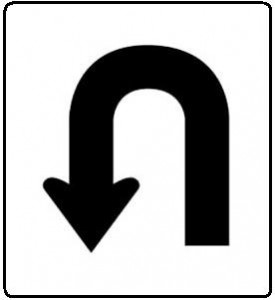

When you are going the wrong way, turn around.

August 2, 2010 by Viki Kind

Filed under Featured, For Patients & Families

When we are making the decisions for those in our care, it is important to make sure that the decision is still working. You may find that you made the best medical decision you could and then the plan didn’t work. When this happens, it is important to reconsider the treatment plan. Otherwise, you’re driving down the wrong road: You can keep driving and driving, but you will never get to where you are going. You need to stop, ask for new directions and then start down a new path.

You may also need to modify your expectations when things don’t work. Sometimes we are so desperate for the plan to work that we can’t bear to see the truth when the plan fails. You are not helping your loved one by continuing treatments that don’t work. You are only subjecting the patient to needless side effects and increased suffering. One thing that doctors may want to do is to try a time-limited trial of a proposed treatment option. “Let’s try it for a few days or for a little while and see how it goes.” This is a really great option. After the set time expires, you can check to see if the decision is working. If it is not working, go back through the decision making process and make a better decision based on the new information about the patient’s changing condition. Don’t be stubborn and keep driving your loved one in the wrong direction. Take this as an opportunity to turn around and get it right.

Have a kind and respectful day.

Patience – Lessons Learned – Viki’s Journey

July 8, 2010 by Viki Kind

Filed under Ask Viki, Featured, Newsletter

Patience – Lessons Learned – KindEthics.com Newsletter

Quote of the Month:

The individual is capable of both great compassion and great indifference. He has it within his means to nourish the former and outgrow the latter.

Norman Cousins

I love when life reminds me of the lessons that I thought I had learned, but then I find out I need a refresher course. This month’s newsletter is about having patience, but not just your average patience, instead good-natured and seeking to understand patience. There are two parts to this story.

The second part first:

Two weeks ago I had to make about 50 phone calls to set up the events for my book tour in July. As I was contacting different groups and reaching out to the community organizations that help those with differing levels of capacity, I was on a roll. Each call was a wonderful opportunity to connect with like-minded people about our common goals. I tend to be a quick person and was enjoying the speed with which I was accomplishing my tasks. Then it happened, I contacted some organizations that focus on helping those who communicate more slowly or differently, and all of a sudden, my world slowed down. The reason being, the people I needed to talk to also suffered from the same issues of communicating differently. What had taken me 10 minutes to accomplish on other calls, now took me 25 minutes.

I had a choice. I could politely excuse myself from the call and just move on to someone else. I could get frustrated or start multi-tasking while I waited for them to say what they needed to say. Or, I could be present, slow myself down, listen differently and be patient. I realized that patience was not about “waiting it out,” but it was about staying connected with an open heart as I remembered I needed to listen differently.

When I did this, I heard amazing things. One gentleman with bipolar disease told me that he hoped others would understand when he said, “I can do it – Until I can’t.” I had never heard this phrase but it was a gift to me because it so clearly explains the needs of someone with a fluctuating mental illness. I had understood the concept as this is exactly what I talk about throughout my book. Keeping people included and empowered, despite their limitations, until those instances when they need us to step in and protect them. But I hadn’t had such an easy way to say it. I am so grateful he shared it with me.

Part 1 of the story:

Back in March, when it was Brain Injury Awareness Month, I was fortunate to connect with a wonderful woman named Tammi Diaz. She suffered a traumatic brain injury when she was hit by a car, but she has overcome her injury, found a new way to be, and is a wonderful advocate for those in her community. I contacted her because I wanted to interview her on my online radio show because I thought it would be great for my listeners to hear first hand from someone who still deals with the effects of a brain injury. When I first spoke with her, I was acutely aware of her slightly slower speech. Not much slower, but just enough to notice. She shared with me her stories about the amazing way she advocates at the state legislature and her passion for improving the public transportation in her community. Coming from a show biz background as a child, I wondered if my listening audience would keep listening once they heard her voice. I realized I might lose some listeners but that was the whole point of the show, to get people to hear from people struggling with brain injuries. (You would have thought that a few weeks later, I would have known that I needed to be patient when I was making all those phone calls. But my own agenda and schedule got in the way. Lesson re-learned.)

I booked her on the show along with the director of the Brain Injury Association in Utah. What a wonderful and inspiring interview. I realized that we don’t hear these types of voices in the media or on television shows. This is a silenced community like so many who struggle with mental illness, dementia, developmental delays etc.

So what is in this message for all of us? I hope that you can remember to slow down and to listen differently when you are talking to someone with a speech or brain disorder. Don’t rush, don’t complete their sentences, don’t get annoyed and don’t think it isn’t worth your time. The gift of understanding that you may receive from someone who experiences the world differently is inspiring. I am so grateful that I got the opportunity to practice what I teach. Each phone call brought a gem of knowledge and a connection with a terrific person. Please role model this kind of behavior for your kids, your colleagues and for others in the public when you can see a store clerk growing impatient with someone with a disability. We can make a difference in the lives of others, by listening with a generous heart and a good-natured attitude.

Have a kind and respectful day.

The medical decision is just part of life’s equation.

So many people ask me what they should be thinking about when making medical decisions. Whether you are making your own decisions or having to make decisions for others, there is a lot to think about.

Your doctor or your loved one’s doctor will talk to you about the medical aspects of any health-related decision. But that doesn’t mean that you are limited to thinking only about medicine. It may be important to consider the financial costs associated with the treatment plan, if the patient’s religion should play a role in the decision and whether there are cultural issues that come into play. Think about the overall picture of your loved one’s life. In The Caregiver’s Path to Compassionate Decision Making, I offer lists of questions to help you understand the whole picture.

It would be nice for the decision to be as simple as asking, “Will the treatment work and what are the side effects?” But life isn’t that simple. What if you were about to make a medical decision that allowed something to be done to the person’s body that was forbidden by the person’s culture or religion? You might have chosen a certain treatment to save her life, but because the patient received that treatment, she will no longer be able to move on to the hereafter. Yes, the medical decision was a good one, but how the decision will affect the person’s life, based on her personal belief system, was not.

If the person you are making decisions for is very religious, then it would be good to find out if there are any religious rules or values that you should consider in your decision making. I know that when I work with my hospice patients, it is important to know if there are certain rites or blessings that have to be performed before the patient’s death. I don’t have to agree with what the person wants, but if I am the caregiver, then I need to do what I can to make sure the person’s religion or culture is respected. I will need to call in the appropriate religious leader to take care of the spiritual needs of this person. If the person is not religious or spiritual, then you will need to respect this and leave religion out of the decision making process.

For most people, the financial costs of the medical treatment will need to be considered or you may be putting the person in financial danger. You may be in charge of making only the healthcare decisions, but you should make sure that you or somebody else checks with the insurance company to find out whether or not it will pay for the treatment and to get the proper authorizations. Don’t let a simple mistake like forgetting to call the insurance company to let them know that your loved one was admitted to the hospital put your loved one in financial distress. Making decisions without using the financial questions could bankrupt your loved one. Our goal of protecting the person should include protecting his or her wallet.

For a list of questions you can use when making decisions, go to the resource page and download the list from the excerpts from The Caregiver’s Path to Compassionate Decision Making – Making Choices for Those Who Can’t.

Have a kind and respectful day.

Great new guide for when you leave the hospital

May 24, 2010 by Viki Kind

Filed under Ethics In Action, Featured

Too often we spend a lot of time thinking about going into the hospital but no time thinking about coming home. The hospital discharge process is when patients are vulnerable to misunderstandings and errors. The patient is feeling sick and not able to listen to the instructions, the loved one may or may not be there, and the nurse rushes through the crucial information. If you can, make sure you have a loved one beside you when the nurse goes over the discharge instructions. If you have questions, ask until you get the answers you need. You can even ask the doctor to tell you what you will need to be prepared for when you go home when you are talking about the upcoming surgery or procedure.

Here is a guide to review and use before you think about going to the hospital.

http://www.medicare.gov/publications/pubs/pdf/11376.pdf

Have a kind and respectful day.